Water Quality. We hear the term in the news, in press conferences, and in editorials surrounding the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton’s proposals to regulate land use primarily in agricultural areas. What is water quality, and what does it have to do with land control?

The Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed Rule, which would redefine what the term “waters of the U.S.” means, has a host of issues. However, the way they are selling their proposed change is in the name of water quality. Thing is, their rule change has nothing to do with water quality, since all the waters in question are already covered by the Clean Water Act. What it does talk about at length, is jurisdiction. The EPA thinks it can do a better job at implementing the provisions of the Clean Water Act than the states can. I don’t know about your state, but Minnesota is doing a great job at identifying impaired waters, establishing a game plan, and achieving it. Personally, I think states, who involve people who live and work in the watershed, are much more effective at protecting water quality than Washington bureaucrats who have probably never set foot in the watershed they are trying to regulate.

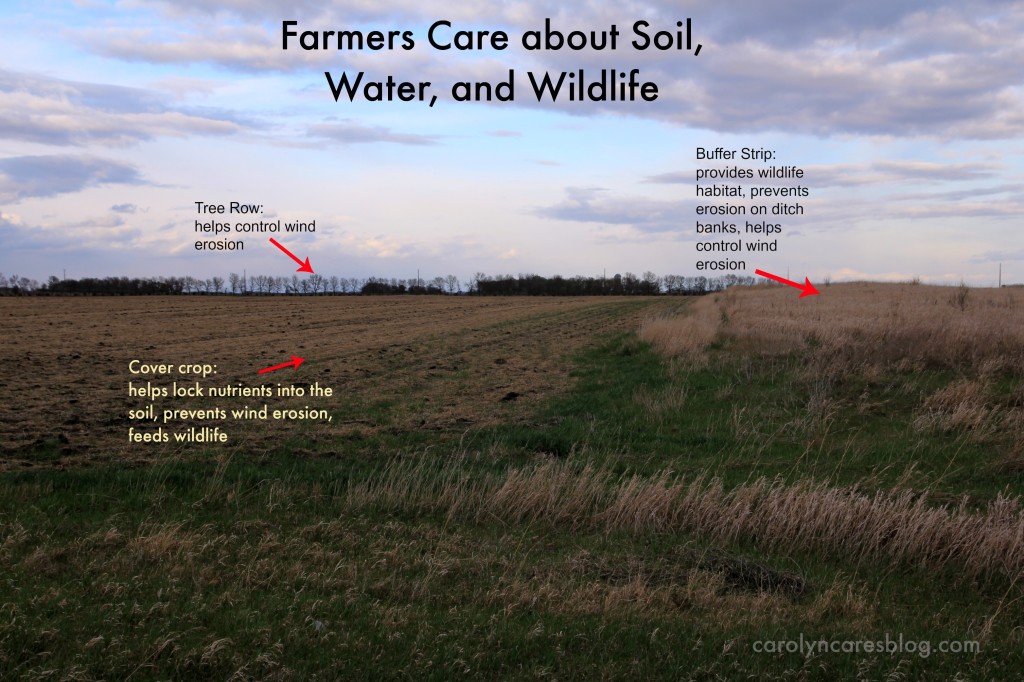

So, what is the point of redefining what constitutes a water of the United States if it isn’t going to change the national water quality standards outlined in the Clean Water Act? Could it be power? Control over agricultural lands? The Rule would broaden the scope of the EPA, and basically puts them in the business of regulating a farmer’s activities, which is not what Congress intended. If your land happens to be within the boundaries of the newly defined significant nexus, you may need a permit from the EPA to do ordinary farming practices. Farmers are already working towards the water quality goals of the watersheds their land is in. On our farm, we have taken advantage of voluntary programs, and federal farm programs that encourage soil and water conservation. We have planted marginal lands into Conservation Reserve Program grasslands, planted living snow fences, and use cover crops. Soil samples, plant tissue samples, and manure samples are tested to determine the correct rate of manure application each fall. We are doing what we can to meet or exceed the standards set for the watershed our land is in.

Redefining the Waters of the United States in the name of water quality is deceiving…a red herring. The EPA is simply looking for more ways to control what happens on the land. Land owned by farmers and landowners who are already complying with CWA standards.

Water quality has also been a hot topic on the state level in a few states lately. In Minnesota, Governor Mark Dayton has asked for a 50 foot riparian buffer strip along all rivers, streams, and ditch banks and everywhere water flows “most of the time”. Sounds good on the surface, but like the EPA’s WOTUS rule, the Governor’s plan has some major flaws.

Farmers are not opposed to buffers. In the right locations, at the appropriate width designed for that particular location, they can be very effective. One-size-fits-all makes no sense if the goal is improving water quality. However, the news media has been blasting agriculture for not doing their part to improve water quality, and is telling the public that we need these buffer strips to achieve water quality. When I read the proposed Senate and House bills, I was puzzled. What exactly is this water quality they are talking about? Under the Purpose of the bill, it lists “protecting water from runoff and erosion; stabilizing soils, shores, and banks; and provide aquatic and wildlife habitat.” (HF1534, MN House of Representatives) Is that what water quality is? If that is the state’s definition of water quality, we can achieve that in without a mandatory, one-size-fits-all 50 foot buffer strip.

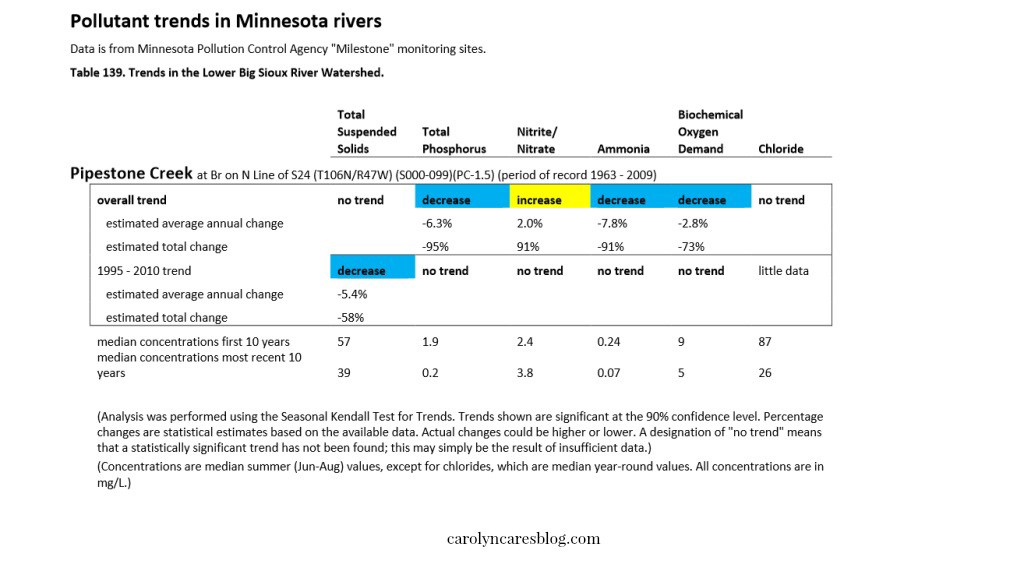

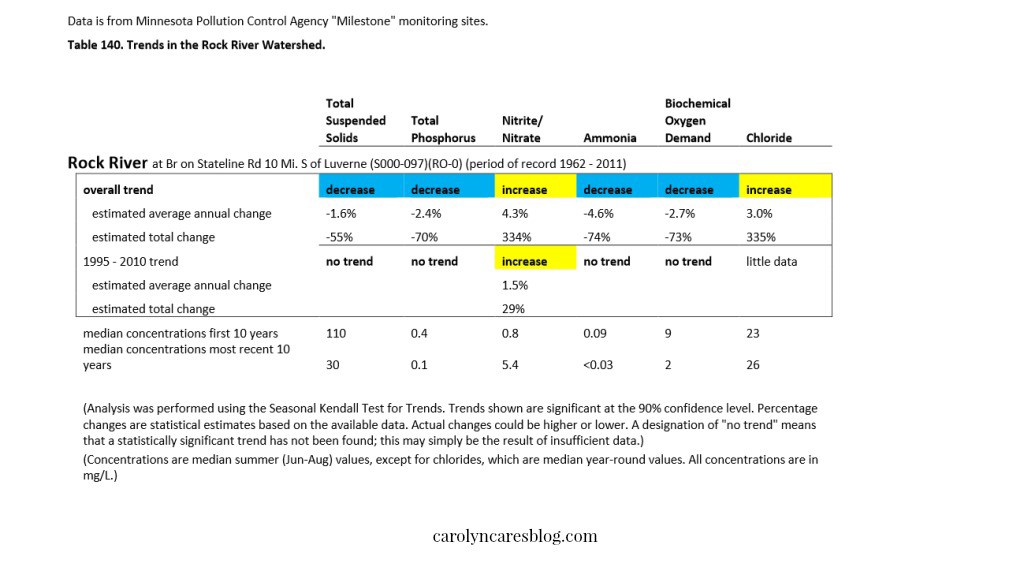

One of the Governor’s reasons for the need for the 50 foot buffer strip is the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency’s latest report on the Missouri River Basin in Southwest Minnesota. As I was reading the full report, a few things stood out. Governor Dayton kept referring to how bad the water quality is, but the same report that had the media blasting agriculture for all the water woes also contained some positive news. Two of the major watersheds had improved water quality over the past 10 years. Pipestone Creek and the Rock River both showed decreases in Total Suspended Solids and Total Phosphorus, two areas of assessment that is mentioned many times in the MPCA’s report.

The other thing that I noticed is that there is no water quality standard for Total Phosphorus in streams, and there are no Nitrite/Nitrate standards in streams or lakes. When reading the chemistry results from the tested waters – where there were water chemistry reports – there were numbers present, but no parameters for TP or Nitrite/Nitrogen. If there are no water quality standards, or water quality goals, how can we know if we have achieved the desired result?

The idea of no water quality standard or goal in the proposed bill was brought up at the Governor’s Buffer Strip Session in Worthington, Minnesota. I was happy the gentleman asked the question, since I had noticed the lack of goals in the bill, but just thought I was missing a point. That question raises another one. If there are no Total Phosphorus standards for streams, how are we to know when we have reached an achievable goal? Is it the historic levels dating back before the European settlements? What if those numbers were historically high, even before the prairies were turned in to farmland? Are we just going to be chasing an unachievable number?

Spring Lake, near Prior Lake recently made a request to the EPA to change the standard for Total Phosphorus from 40 ppb to 60 ppb after a lake sediment core was studied, and it found that Spring Lake historically was high in Total Phosphorus. So, if TP was high before the land surrounding Spring Lake was turned into farmland, is it agriculture solely to blame? I don’t think so.

It remains that there are no true water quality standards set out in Governor Dayton’s Buffer Strip bill. Even when farmers are accused of not doing their part to improve water quality, the MPCA’s own documents show otherwise. So, if there is no true water quality standard in the bill, using water quality as the selling point is deceiving…a red herring. What is it that the Governor truly wants? More land.

In December, the Governor held a Pheasant Summit to address the decline in the pheasant population in Minnesota. It was there that the first mentions of a 50 foot buffer strip plan were heard. When the Governor announced his plan a few weeks later, it was not met with much enthusiasm. In January, the buffer strip idea was introduced as a way to increase water quality. Water quality is an emotional subject, and has been used as a rallying cry for the Governor’s plan to put the Department of Natural Resources in charge of those 50 foot buffers on privately owned land. In the name of water quality, farmers have been raked through the mud and have been characterized as being uncaring polluters. As mentioned above, we do many things to improve water and soil conservation on our farm. We care about water quality just as much as our friends in town do. We drink the water from our wells, we bathe in it, we use the water for recreation, and we depend on the rain for our crops. Jonathan and I are not unique in that aspect.

If the EPA or the Governor were truly more interested in water quality than control of property rights, they would support incentives for farmers, businesses and non-farmer land owners that allow for an individualized approach that takes into account the unique features of that property. Both entities need to quit deceiving the public, and call their proposals what they really are: A quest for the control of the landowner’s private property.